Your cart is currently empty!

- At the second reading of the Domestic Abuse Bill held on 5th January 2021, the issue of Parental Alienation was raised by a handful of peers.

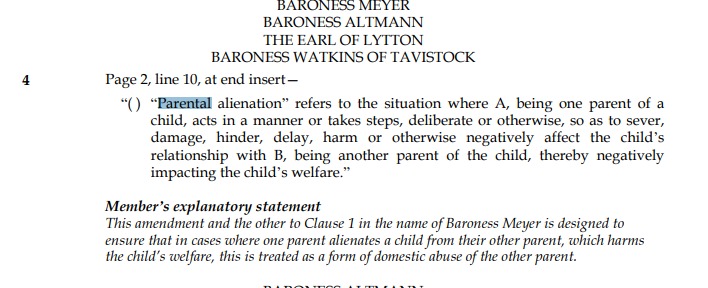

- It has been tabled as an amendment that parental alienation should be formally included in the Bill, defined as a form of domestic abuse. Domestic abuse survivors with children (referred to within this briefing statement as ‘survivor families’) have grave concerns about the consequences of the inclusion of parental alienation within the definition of domestic abuse.

- To understand the dangers of including parental alienation as defined domestic abuse it is important to understand how this allegation is used, how frequently it is levelled at survivor families and the apparent purpose of these allegations in the context of family court. Just over 95%[1] of survivor families reporting domestic abuse, have a counter allegation of parental alienation levelled at them in court. It appears the purpose of many of these allegations of parental alienation in response to domestic abuse allegations, is that it is used as a deflection or a defence by perpetrators with alarming frequency.

- Dr Adrienne Barnett’s findings in Barnett, A. (2020) ‘A genealogy of hostility: parental alienation in England and Wales‘ showed “A clear pattern emerged of, initially, parental alienation syndrome and subsequently PA being raised in family proceedings and in political and popular arenas in response to concerns about and measures to address domestic abuse. The case law revealed a high incidence of domestic abuse perpetrated by parents (principally fathers) who were claiming that the resident parents (principally mothers) had alienated the children against them, which raises questions about the purpose of PA”[2].

- Survivor families experience of parental alienation allegations in the family court are that it is routinely used to successfully deflect from the conduct of the perpetrator. It’s most often an allegation levelled at those bringing evidence of domestic abuse into court. In fact, just over 95%[3] of those bringing domestic abuse allegations into court report parental alienation being counter alleged, apparently in a bid to minimise or completely obscure evidence or allegations of abuse.

- Safeguarding survivor families must be paramount. Allowing parental alienation to be classified as domestic abuse is likely to cause a ‘checkmate’ for parents seeking to limit contact with an abusive parent for safeguarding reasons. The risk to children could not be effectively managed if there is evidence of abuse, but a counter allegation of parental alienation. It is an unmanageable level of risk for survivor family to have their hands effectively tied in seeking to reduce or limit contact with a person who has harmed them. By including parental alienation in the Bill’s definition of domestic abuse, it could leave state agencies and actors powerless to implement protective measures for children at risk of domestic abuse, as the act of limiting the abusing parent could be viewed as alienating (and therefore abusive), as per the proposed amended definition.

- Implementing protective measures for a child in accordance with their United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) 1989 rights, and in particular their Article 19 rights, may require the state to reduce contact with an abusing parent. The state and relevant agencies must have mechanisms to allow them to minimise risk for those children, without the risk of a parental rights stalemate occurring on the issue of parental alienation. For agencies seeking to keep children safe, including parental alienation in the definition of abuse could prevent them implementing protective measures. If the state is seeking to limit contact between a child and a parent who has harmed, with parental alienation defined as a form of abuse, it could be upheld that the state is also abusive.

- Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) 1989 enshrines the rights of children to have their perspectives included and taken into account in legal proceedings that affect them. Section 1(3) of the Children Act 1989 requires that the courts consider “the ascertainable wishes and feelings of the child concerned (considered in the light of his age and understanding)” in children cases[4]. By including parental alienation in the definition of abuse, children will not be safe to report negative feelings about a parent who has harmed, as it could be construed as abusive and ‘alienating’ to do so.

- Further, the Ministry of Justice Harm Report found that ‘The weight of evidence from both research and submissions suggests that too often the voices of children go unheard in the court process or are muted in various ways[5]. #thecourtsaid surveyed over 900 families in December 2020 and found that 81% of children in cases involving a parent who has harmed, were frightened of that parent. 71% of children made it known that they were frightened, and 91% report their negative feelings were ignored by the family court. Further, 85% said that they were then forced or coerced into risky contact with the parent who had harmed. Just over 95% of survivor families have had allegations of parental alienation made against them, for seeking to limit children’s contact with a parent who has harmed.[6]

- The consequences for children can be catastrophic and can include being separated from their safe parent. Survivor families report that an allegation of parental alienation in the context of abuse has the effect of entirely obscuring the child’s voice. For example, once parental alienation has been alleged, if the child reports fear of the parent who has harmed, their voices can be translated rather than transmitted. The result of the application of parental alienation theory is risky because anything the child says in this context, can be viewed as being from the resident parent rather than the child’s own wishes and feelings. Professionals subscribing to the theory view a child’s voice as polluted, if the child is seeking to limit contact with a parent who has harmed. This creates an atmosphere where children are in danger of having their concerns minimised or entirely ignored.

- Around the world, this issue has been addressed by CEDAW. The Platform members addressed this issue during the conference on “Women’s rights at the Crossroads: strengthening international cooperation to close the gap between legal frameworks and their implementation” hosted by the Council of Europe on May 24th 2019 in Strasbourg. They call upon States “to pay particular attention to these patterns and to take the necessary measures to ensure implementation of international standards that require that intimate partner violence against women is thoroughly weighed in the determination of child custody”

- CEDAW outlines that the Istanbul Convention is ‘the only legally binding instrument on violence against women that has an explicit provision on child custody in such situations’.[7] Its article 31[8] requires States to “take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure that, in the determination of custody and visitation rights of children, incidents of violence covered by the scope of this Convention are taken into account” and that “the exercise of any visitation or custody rights does not jeopardize the rights and safety of the victim or children”. The expert body monitoring the implementation of the Convention’s standards (GREVIO), has found evidence of gender bias towards women in custody decisions and lack of attention paid by courts to patterns of abuse by fathers in all 10 States parties monitored so far”[9]

- “The experts further discouraged the abuse of the “Parental Alienation” and of similar concepts and terms invoked to deny child custody to the mother and grant it to a father accused of domestic violence in a manner that totally disregards the possible risks for the child. In this regard, the Committee of Experts of the Follow-up Mechanism to the Belem do Para Convention (MESECVI), in the 2014 Declaration on Violence against Women, Girls and Adolescents and their Sexual and Reproductive Rights, recommends to explicitly prohibit, during the investigations to determine the existence of violence, “evidence based on the discrediting testimony on the basis of alleged Parental Alienation Syndrome”. The experts also expressed concern for the recent inclusion of “parental alienation” as an index term in the new WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as a “Caregiver-child relationship problem” that could be misused if applied without taking into consideration above-mentioned international standards that require that incidents of violence against women are taken into account and that the exercise of any visitation or custody rights does not jeopardize the rights and safety of the victim or children. Accusations of parental alienation by abusive fathers against mothers must be considered as a continuation of power and control by state agencies and actors, including those deciding on child custody.”[10]

- In light of these significant concerns, survivor families urge the committee to reject the following amendment:

[1] #thecourtsaid poll Jan 2021

[2]Barnett, A. (2020) ‘A genealogy of hostility: parental alienation in England and Wales‘

[3] #thecourtsaid survey January 2021

[4] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/895173/assessing-risk-harm-children-parents-pl-childrens-cases-report_.pdf

[5] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/895173/assessing-risk-harm-children-parents-pl-childrens-cases-report_.pdf

[6] #thecourtsaid survey ‘Children at Risk’ December 2020

[7] (https://rm.coe.int/final-statement-vaw-and-custody/168094d880)

[8] https://rm.coe.int/168046031c pg 16 (Article 31, Istanbul Convention)

[9] (https://rm.coe.int/final-statement-vaw-and-custody/168094d880)

[10] (https://rm.coe.int/final-statement-vaw-and-custody/168094d880)

Leave a Reply to greydog5Cancel reply